Are Algorithms the Answer? Vol 2

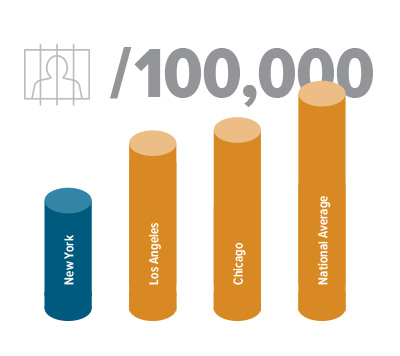

Pre-trial detention is both costly and often disproportionately leveraged against minorities and those with lower socio-economic means. Courts nationwide are looking to algorithms to determine whether a defendant should be detained pending trial. The goal of using algorithms is twofold: reduce the population of pretrial detainees and help judges make better decisions regarding the need to detain a defendant.

Across the United States, criminal justice policymakers, practitioners, and advocates have raised concerns about the large number of people who are detained in local jails while waiting for resolution to their criminal charges. While some defendants are held because they are deemed likely to flee or commit additional crimes if released, many others do not pose a significant risk and are held because they cannot afford to pay the bail amount set by a judge. Incarcerating these relatively low-risk defendants is costly to taxpayers and disrupts the lives of defendants and their families, many of whom have low incomes and face other challenges. To address this situation, some jurisdictions are experimenting with new approaches to handling criminal cases pretrial, with the overarching goal of reducing unnecessary incarceration while maintaining public safety.

Currently, most jurisdictions in the United States work on a bail/bond system. The judge generally looks at the information in front of him/her in the defendant’s file and is forced to decide whether the defendant will be released on his/her own recognizance or if they will be given the opportunity to post bail pending trial. In many cases, there is a chart that is used to determine the amount of bail that is to be set based on the level of the offense and the defendant’s criminal record. Another factor considered is the defendant’s age and ties to the community, i.e. family, job, housing. Research has proven that the bond system tends to be biased against those who are poor and, often, minorities and the homeless. Intuition is also often biased against the same populations. Inserting a data-driven alternative is a good step toward reform and a more just system.

Simply put, those with money are more likely to be able to post whatever bail is set, avoid jail time, and afford a lawyer to help reduce the charges. Those who are poor can’t afford the bail or time off the job to fight the charges; therefore, they are more likely to take a plea whether they are guilty or not, thus ending up with a lengthier criminal record. This, of course, sets them up to be ineligible the next time they get arrested whether for valid or invalid charges. It is a vicious cycle.

During the last few years, increased awareness of the economic and human toll of mass incarceration in the United States has launched a reform movement in sentencing and corrections. According to Arnold and Arnold [“Fixing Justice in America,” Politico Magazine], this remarkably bipartisan movement is shifting public discourse about criminal justice “away from the question of how best to punish, to how best to achieve long-term public safety.”

It seems from the collective research that for the algorithm to be successful, the tool not only needs to be valid but also properly implemented. This includes intensive training on the tool, its goals and limitations, and consistent use at every level—from the officer utilizing it and entering the data in the system to the judge who determines the appropriate pre-trial action.

Kentucky, which has been working on reform of pre-trial detention for over a decade, struggled until 2013 when it added the PSA tool and training for all parties involved. It has since seen great success. A balance needs to be realized between what the tool suggests and the judge’s intuition. But in any case, a proprietary bail system that grossly over houses the poor needs to be eliminated. Putting at-risk community members in touch with the appropriate resources to help them be contributing members of society is for the greater good. Research supports that this can be accomplished without creating harm to society and for defendants still appearing for court appearances as evidenced in Kentucky and New Jersey.

Research has proven that the bond system tends to be biased against those who are poor and, often, minorities and the homeless. Intuition is also often biased against the same populations. Inserting a data-driven alternative is a good step toward reform and a more just system.

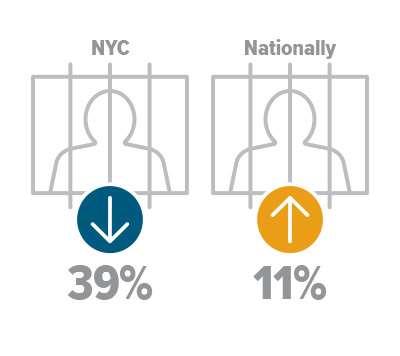

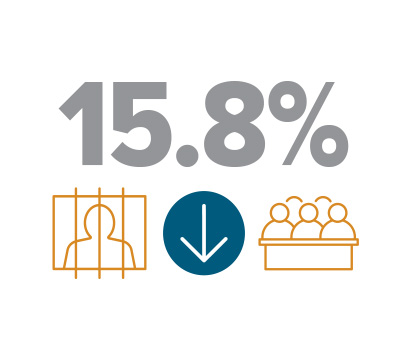

According to New Jersey’s state-reported data, between January 1 and July 31, 2017, the state of New Jersey has seen its pretrial jail fall by 15.8 percent. That is an impressive drop in under a year. That translates to 2,167 fewer people held in pretrial detention on July 31, 2017, than at the same time in 2016. That’s more than 2,000 people who have not been convicted of any wrongdoing, and who get to live at home with their families and carry on their normal lives rather than live in a jail cell. These same people also stand a better chance of keeping their jobs and their kids, and their lives aren’t unnecessarily disrupted while they are locked up before even being convicted. It is important to note that during this same time, New Jersey’s crime rate fell. According to the New Jersey State Police, violent crime in January through August 2017 was 16.7 percent lower than during the same period of 2016. Murder fell by 28.6 percent, assault by 13.3 percent, robbery by 22 percent. By contrast, violent crime only fell 4.3 percent in 2016, and didn’t move in 2105.

It’s far too soon to say if bail reform contributed to the big year-to-year drop. But at the very least, bail reform hasn’t been accompanied with some dramatic increase in danger or crime. More people are free, and more people are safe.

Kentucky’s courts have used the PSA-Court to help identify low-risk defendants who pose little threat to public safety and are therefore suitable for pretrial release. Since implementation of the PSA-Court, and as compared to the four years prior to July 1, 2013, the new criminal activity rate has dropped significantly. Kentucky is now detaining more high-risk and potentially violent defendants, while more low-risk defendants are being released. And crime is down.

We are only scratching the service on how algorithms, research, and data-driven decision making can help reform the pre-trial process. This is where academic partnerships and alliances with agencies in our community can make a difference.

Based on the research, considering people are going to make errors and no system is perfect, it seems like this approach is a good start at taking out some of the bias and making the system a bit fairer, particularly for poor, non-violent offenders. Furthermore, it may go a long way toward helping our communities; if we get people in touch with the resources they need rather than put them in a cage, they are more likely to productively contribute to society.

DOWN THE ALGORITHM RABBIT HOLE

In fall 2017, Gretchen Schmidt read an article about New Jersey’s adoption of algorithms in determining pre-trial sentencing. The concept of bail reform appealed to Schmidt, who prior to her career in higher education, worked in the legal field. In fact, during law school, she worked at a sheriff’s office where one of her responsibilities was conducting legal research with inmates two to three times a week.“While using data to inform sentencing decision is not new, the concept of using data-driven tools to help remove some of the apparently intrinsic bias in the current bail/bond system was appealing to me,” says Schmidt.

In February 2018, she presented on the use of algorithms in the pre-trail sentencing process at the 55th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences. The Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences is an international association established in 1963 to foster professional and scholarly activities in the field of criminal justice. It promotes criminal justice education, research, and policy analysis within the discipline of criminal justice for both educators and practitioners. Schmidt was part of a panel presenting papers related to issues with pre-trial detention.

There are extensive writings about algorithms being used in different ways and phases of the criminal justice process. “As I began my research, I did exactly what I caution my students against: I kept getting led down rabbit holes,” recalls Schmidt.

One rabbit hole she found herself exploring relates to the correlation between being detained pre-trial and the likelihood of being arrested. Related is research regarding the likelihood of someone detained pre-trial being sent to jail. “The theory is that if you are detained, you are more likely to take a plea and get a shorter sentence or, in best case scenario, time served. This, of course, leads to the last rabbit hole, the likelihood of pleading guilty to something you didn’t do because you don’t have the time or money to defend yourself,” she explains. These are serious issues to be considered when looking at pre-trial detention and the bail/bond system, and Schmidt was determined to see if algorithms were a solution.

Schmidt came to the conclusion that “in order for the algorithm to be successful, it needs to be properly [implemented], which includes intensive training on the tool, its goals and limitations, and consistent use at every level from the officer utilizing it and entering the data in the system, to the judge who determines the appropriate pre-trial action.” Her research supports this can happen. Schmidt reports that Kentucky added a public safety assessment tool and training for all parties involved in 2013 and, since then, has achieved great improvement in pre-trial detention. “In any case, a proprietary bail system that grossly over-houses the poor needs to be eliminated,” she says. – by Jenna Kerwin