Keeping a Tradition Alive

This article was originally published in Live & Learn Magazine, Vol. 14, No. 1, in 2011.

Blending present-day technology with traditional artistic techniques, artist Len Tantillo brings history to life in his many paintings. Much like Excelsior College’s use of technology to deliver educational opportunities to students, Tantillo has embraced digital modeling in conjunction with conventional painting techniques to offer rich depictions of the past.

In 2011, Excelsior President John Ebersole commissioned Tantillo to create a historical work in honor of the College’s 40th anniversary. The artist, widely known for his insightful research to create deeply perceptive historical works, was challenged by the task. Forty years, after all, is not that old in a historical sense, and Excelsior doesn’t have stately, ivy-covered brick buildings on its campus that might create an obvious artistic backdrop. Tantillo explained the conundrum, “Excelsior isn’t a place. Excelsior is an idea. So, how do you paint an idea?”

“That refrain of a college without walls kept kind of echoing in my head. You know, education, but not in a specific place” –Len Tantillo

A skilled researcher, Tantillo started with his own instincts and imagination. His first thoughts were along the lines of itinerant professionals and doctors who made house calls. He thought, “I wonder how many other services like that there could have been?” With the seed planted, he began his exploration. “That refrain of a college without walls kept kind of echoing in my head. You know, education, but not in a specific place,” he recalled.

Two Movements Spark an Idea

His investigation began simply, with keywords such as education, history, and night school and uncovered results that helped frame the concept from which the work, Keeping a Tradition Alive, was born. Tantillo learned of two educational endeavors — The American Lyceum and the Chautauqua Movement — that spoke to the roots of non-traditional education, historical forebears to the innovative idea that became Excelsior College.

Much like Excelsior brings education to students, rather than the students coming to a physical classroom, the American Lyceum Movement featured traveling educators. Yale graduate Josiah Holbrook founded the movement in the mid-1820s, traveling across the eastern U.S. to promote the concept of education for adult learners. Initially aimed at farmers, the lyceums by the 1840s had become more professional institutions with lectures from famous intellectuals such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Frederick Douglass, Henry David Thoreau, Daniel Webster, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Susan B. Anthony.

Tantillo recalled sharing his concept with President Ebersole. “We started talking about this idea of the American Lyceum and I made a sketch right on the spot” (shown below). The artist envisioned a small, diverse group of people, gathered in a cornfield at night, after their work was done, much like the working adults who make up Excelsior’s average student. “It was this idea of nighttime and glowing light and engaged individuals participating in some sort of educational event,” he added.

Lyceums flourished until the outbreak of the Civil War. Following the war, they blended into New York State’s Chautauqua Movement of the 1870s. The original Chautauqua Lake Sunday School Assembly in western New York, founded in 1874 by John H. Vincent and Lewis Miller, began as a program for the training of Sunday-school teachers and church workers. At first entirely religious in nature and held outdoors, the program gradually broadened to include general education, recreation, lifelong learning, and popular entertainment. In later years, the summer lectures and classes were supplemented by a year-round, non-denominational course of directed home reading and correspondence study.

Stage is Set: Modeling Begins

With the concept for the work in hand, Tantillo was ready to plan the scope of the piece. With a degree in architecture from the Rhode Island School of Design, he began his career as an architectural designer and later worked as a freelance architectural illustrator. A commission to depict a series of 19th-century structures from archaeological artifacts and historical documents in 1980 was the genesis of his historical painting career, and in 1984, he left commercial art altogether to work full time in fine art. Yet his architectural background serves as a foundation on which to build his art, as he often creates models as a reference. When his work depicts events that predate photography, these models afford him a means to recreate history based on his research.

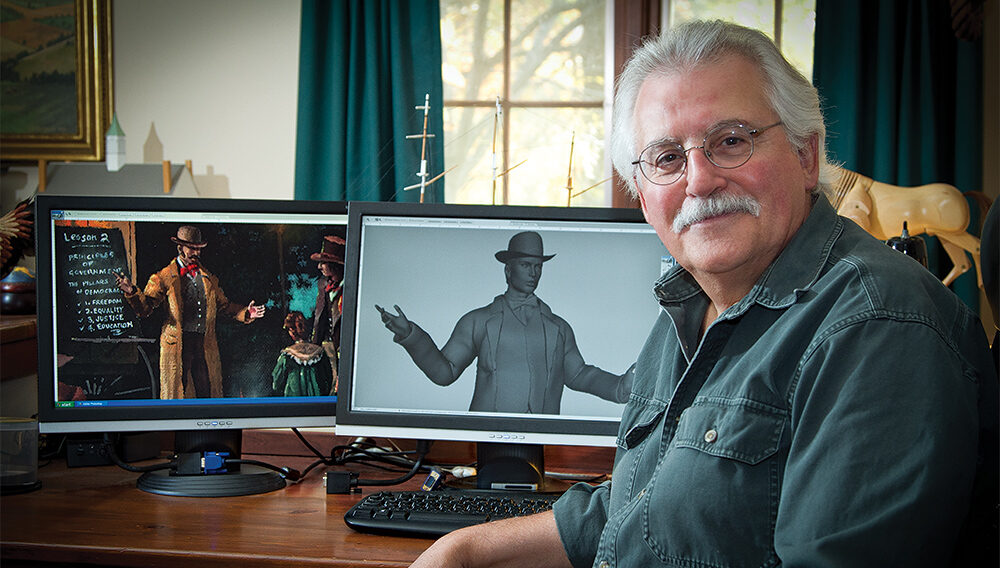

His early structural models were made out of cardboard, paper, and cloth, and he often used human models as well. Finding appropriate costumes for his subjects could prove challenging, sometimes requiring that he sew the meticulously researched attire himself. But about 10 years ago, he added computer modeling to his art box. Using the 3-D modeling and graphics software Rhino and Maya, he can create not only the setting for a piece, but individuals and their clothing as well. “The computer allows me to take a human form, manipulate the facial features, create hair styles and clothing,” he described.

The Excelsior-commissioned work took Tantillo approximately five months to create, and a large part of that time was devoted to perfecting the computer-generated model. “It’s a tremendously powerful tool,” he said of the software. “It allows me to go places I could never go before. The subjects were just too complex. But now that I have these skills to do the digital modeling, it has expanded my horizons tremendously.” Once the digital work was done, Tantillo could begin the process of putting brush to canvas, marrying technology and tradition to produce a timeless piece of artistic beauty and historic significance.

The Painting: An Idea Takes Shape

The painting captures both the rural roots of adult education in America, as well as the spirit of the extraordinarily committed educators who traveled from community to community to share their knowledge.

This early form of night school portrays education being delivered to working adults. The many lanterns in the scene symbolize the flame or lamp of knowledge, and the promise inherent in education to bring students out of the darkness and into the light. Those depicted in this painting represent the forebears of Excelsior students today — adults of all ages, veterans and active military, ethnic minorities, men and women, and, most prominently, a nurse, who, carrying a lantern, evokes the image of Florence Nightingale. Given that Excelsior College has the largest nursing program in the country, it is appropriate that she is in the foreground.

A trunk with the name “R.E. Bennett” inscribed on its side sits on the ground, next to the instructor’s wagon (detail below). Tantillo added this detail in homage to an educator who helped light his interest in history. “Robert Bennett was my favorite history teacher, my favorite teacher of all time,” he explained. Bennett’s enthusiasm for history made a lasting impression on the artist. He added, “When you went into his class, you didn’t know what the lesson was going to be, but you knew it was going to be exciting and interesting. And he always made you think about it; he would try to take you back into the world at that time.”

The work, Keeping a Tradition Alive, illustrates lessons learned from a time when formal American adult education was in its infancy. The torch has been passed, from the American Lyceum movement to Excelsior College and others. As the College celebrates four decades of providing educational opportunities to working adults, it is important to not forget those who blazed a trail, and thanks to the artistic vision of Len Tantillo, it will always be remembered. What does Tantillo hope people will take away from this work? “The idea, at the most ground level, that people’s desire to learn is universal and timeless. If the desire is strong enough, you’ll make time to do it.”