A New ERA?

“We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal” –Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, Seneca Falls Convention, 1848

There is no question about it — the U.S. Constitution of 1789 did not include women in “We the People.” Efforts to rectify this inequity range from the famed declaration at Seneca Falls in 1848 through the first-, second-, and third-wave feminist movements to the present. According to recent polling data by the ERA Coalition, 80 percent of Americans today mistakenly believe the U.S. Constitution already guarantees men and women equal rights. When they discover it does not, 94 percent support an amendment to guarantee it. The numbers indicate overwhelming support by both men and women from across the political spectrum. Why then does no such amendment exist?

An Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the Constitution passed easily through both houses of Congress in 1972 and made its way to the states for ratification. The wording of the ERA was a simple statement guaranteeing equality under the law:

Within a year, 30 of the 38 necessary states had ratified, and passage seemed all but assured. But the ERA’s progress through the states unraveled over the course of the 1970s and 1980s because of a growing backlash, which led to the amendment’s eventual failure in 1982. How did this clash come to pass? Why did Americans, especially women, disagree so profoundly about the idea of constitutional equality of the sexes? Could the ERA still pass in our current era, and if so, what changes could it bring to our society?

The Early ERA Movement

In the wake of the 19th Amendment in 1920, which guaranteed women the right to vote, many suffragists — now organized and politically mobilized — did not simply return to the domestic sphere. The National Women’s Party, led by famous suffragist Alice Paul, pursued a new phase of activism: lobbying for an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution. An ERA was first introduced to Congress in 1923, stating simply: “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.” Paul believed that the 19th Amendment alone would not be enough to assure equal protection of the laws for women (nor would the 14th Amendment, as some argued), necessitating passage of the ERA to “remove every artificial handicap placed upon women by law and by custom.”

Paul’s ideas were popular among white, middle-class women in the 1920s and 1930s but did not resonate widely. Working-class women, in particular, feared the ERA would overturn protective legislation for women in the workplace. For example, Mary Van Kleeck, the first head of the Women’s Bureau in the U.S. Department of Labor, argued against the ERA, stating: “some of our laws which do not apply alike to men and therefore appear to perpetuate legal discriminations against women — such as mother’s pensions and certain provisions for the support of children — do so only superficially. Actually, these laws are intent to protect the home or to safeguard children.” In addition, African American women argued the focus on the ERA did nothing to address the more pressing issue of disfranchisement of their voting rights in the South.

Bipartisan Support

The ERA gained some momentum in 1940 when the Republican Party endorsed it in its platform and the Democratic Party followed suit in 1944. Still, the amendment remained in the shadows of mainstream politics in the middle part of the century, in part because of continued opposition by the labor movement. A turning point came with the 1964 passage of the Civil Rights Act, which included Title VII, prohibiting discrimination in employment on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, or sex, essentially nullifying many protective labor laws. The addition of sex was proposed by a segregationist Congressman hoping to use it to tank the bill (to no avail). Unfortunately, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) created to enforce the Civil Rights Act rarely intervened in sexual discrimination grievances. The director Herman Edelsberg viewed the sex clause as a joke, stating “there are people on this commission…who think that no man should be required to have a male secretary and I am one of them.” Nevertheless, by the end of the decade, major labor organizations like the UAW and AFL-CIO had largely reversed their positions on the ERA.

1982 ERA demonstrators in front of the Florida Supreme Court —Tallahassee, Florida.

The growing second-wave feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s returned the ERA to the forefront of American consciousness. The feminist movement led to considerable personal and political gains for women in this era and women’s rights found support on both sides of the aisle; it was neither strictly the realm of Democrats or Republicans. The largest feminist organization of the era, the National Organization of Women (NOW), passed a Bill of Rights in 1967 which included support for the long-sidelined ERA. In 1972, the Equal Rights Amendment finally passed through Congress. It had strong bipartisan support, including endorsement by current president Richard Nixon. By all accounts it was nearly a “done deal,” merely awaiting ratification by the necessary three-fourths of the states within seven years to become the 27th Amendment.

Backlash and Failure

So how did a popular, bipartisan amendment fail? The answer lies in the shifts occurring within the Republican Party in this era. The 1960s and 1970s were a period of significant realignment for the GOP, driven in part by debates about feminism and the family. Conservative Sen. Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign, along with the rising popularity of Ronald Reagan, represented a challenge to the moderate Rockefeller Republicans. This era also saw the Republican Party pursue disaffected Democratic voters, particularly those in the South and the suburbs who opposed the social changes of the 1960s brought by the civil rights movement, feminism, counterculture, and the anti-war movement. This shift coalesced into the rise of the “New Right”— a diverse coalition of social conservatives motivated by their positions on race, religion, family, or gender roles. Many social conservatives felt called to action in opposition to the gains of the feminist movement, particularly the 1973 Supreme Court decision legalizing abortion, Roe v. Wade. Republican feminists, meanwhile, who were committed both to small-government conservatism and women’s rights, found themselves in a precarious position within their own party. Many prominent Republican feminists, like Jill Ruckelshaus and Mary Dent Crisp, continued to push back against the New Right coalition from within, insisting feminism and Republican values were not antithetical, and the Republican Party, the original home of suffrage and the ERA, ought to continue to support women’s rights legislation.

But increasingly, Republican feminists lost ground to anti-feminist leaders in the party. Foremost among these was Phyllis Schlafly, who rose to fame with her book “A Choice Not an Echo,” written in support of Goldwater in 1964. Contrary to popular misconception, Schlafly was not always opposed to the ERA; she even thought it might be “mildly helpful.” However, in 1972, after a friend encouraged her to take a deeper look, she came out in strong opposition and formed the organization STOP ERA (an acronym for “Stop Taking Our Privileges”). Part of her opposition stemmed from her belief in limited government, fearing that the amendment would grant too much power to the federal government to interfere in the traditional family. Her STOP ERA movement resonated across the country with socially conservative religious women who opposed challenges to traditional gender roles. Schlafly stoked fears of change by highlighting the potentially wide-ranging ramifications of the amendment. She argued: the ERA would force men and women to share public restrooms, lead to women being drafted into combat, hurt women’s custody rights in divorce cases, and lead to same-sex marriage and unlimited abortion rights. She attacked not just Democrats, but members of her own party for their failure to recognize the threat of the ERA. Schlafly especially pulled no punches in critiquing so-called “women’s libbers” who supported the ERA because, she argued, they “hate men, marriage, and children.”

By the late 1970s the amendment had lost considerable momentum due to STOP ERA’s pressure on state legislators. Thirty-five states had ratified, three shy of the goal. In the meantime, five additional states rescinded their ratification, an outcome of questionable legality. Proponents of the ERA continued to campaign in favor of the amendment that would, as they argued during the International Women’s Year Conference of 1977, “enshrine in the Constitution the value judgment that sex discrimination is wrong.” They countered Schlafly’s assertions by arguing the ERA “will NOT change or weaken family structure” and would not affect same-sex marriage laws, abortion laws, or require unisex bathrooms. They noted the broad support for the ERA among both Republicans and Democrats, including by the last six presidents of the United States.

Approaching the 1979 deadline, with pressure from feminists and a NOW-sponsored boycott of unratified states, Congress extended the ratification deadline until 1982. But the three remaining states never came. The realignment of the Republican Party toward the New Right was a certainty by the 1980 presidential election. Indeed, the 1980 GOP platform was the first to not include support for the ERA in 40 years. In 1982, still three states short, the amendment failed. At the time of the amendment’s failure, most Americans still supported it. Even in unratified states like North Carolina, Florida, and Illinois, a solid majority favored its passage.

The ERA Today and Tomorrow

ERA proponents believe a path toward ratification still exists today. The most promising is the “three state strategy” wherein legal scholars believe three additional states could ratify to reach the required 38 total and then Congress could repeal the original ratification deadline. While this would certainly ignite debate around the issues of the rescission and ratification deadlines, it’s a possibility that has come much closer to fruition recently as Nevada and Illinois became the 36th and 37th states to ratify in 2017 and 2018. ERA bills have also been introduced in other unratified states, including Arizona, Florida, North Carolina, Utah, Virginia, and Georgia.

A scene from a rally on March 22, 2012, at the U.S. Capitol marking the 40th anniversary of Congress’ passage of the Equal Rights Amendment.

Many of Phyllis Schlafly’s talking points against the amendment, regardless of their validity, are no longer contemporary concerns — women are no longer excluded from combat and politicians on both sides of the aisle support women registering for the Selective Service, gender-neutral bathrooms are common, Obergfell v. Hodges (2015) legalized same-sex marriage, and women no longer receive custody preference in divorce cases. No longer able to fall back on Schlafly’s old arguments against it, some critics now charge the ERA is simply no longer necessary. Indeed, without the ERA, other laws have closed gaps in sex discrimination, including Title IX of the Education Amendments (1972), the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (1974), the Pregnancy Discrimination Act (1978), the Violence Against Women Act (1994), and the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act (2009). In addition, 24 state constitutions now have provisions guaranteeing equal rights on the basis of sex.

Yet there are still no guarantees of equal rights at a constitutional level and legislation can be overturned much more easily than a constitutional amendment. While some people have argued that the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment already guarantees equality in the Constitution, an argument made continuously since the days of Alice Paul, the problem is that it is subject to differing interpretations by the courts and not a clear guarantee. As the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia argued in 2011, “certainly the Constitution does not require discrimination on the basis of sex. The only issue is whether it prohibits it. It doesn’t.”

Discrimination against women occurs daily in our current society, and legal and judicial remedies have proved incomplete in addressing it. Legal solutions to sex discrimination have failed in such areas as pregnancy discrimination, domestic violence, and pay inequality. For example, courts have upheld the constitutionality of paying a woman less than a man doing the same work because the woman’s salary in her previous job was less than the man’s. As a result, “women can expect to earn much less than men over the course of their careers — anywhere from $700,000 to $2 million less,” says Jessica Neuwirth, president of the ERA Coalition, in her book “Equal Means Equal: Why the Time for an Equal Rights Amendment Is Now.”

Would passage of the ERA lead automatically to a sex-blind and equal society? That’s not likely, at least at first. However, as Neuwirth, articulates, “the way our Constitution works, we cannot say with certainty what exactly the ERA will or won’t do… It is for Congress and state legislators to pass laws, and for courts to interpret them. What we can say with certainty is that the ERA will give the courts a new standard, a clear and strong statement of sex equality.”

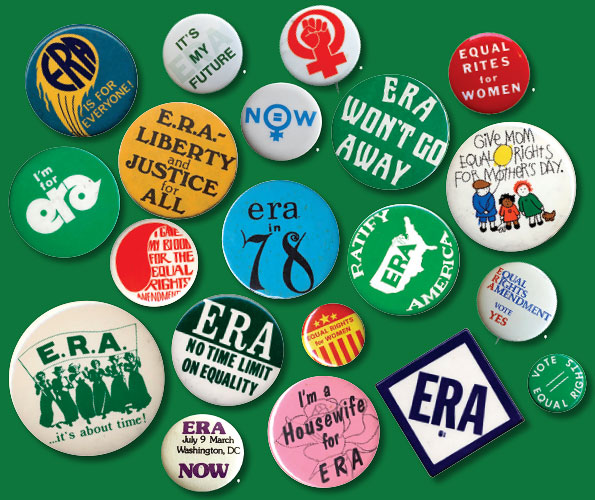

Button images are from the collection of Jo Freeman, except ones marked with an asterisk.

It would likewise help to put the U.S. back on equal footing internationally with the 187 nations (nearly every nation on Earth) that ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and the 139 with sex equality provisions in their constitutions. As Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg argued at a Duke University Law School talk in 2005, “Every constitution written since the end of World War II includes a provision that men and women are citizens of equal stature. Ours does not.”

Perhaps the most compelling reason to seek ratification likewise comes from Justice Ginsburg’s 2005 remarks at Duke, articulating its importance for the next generation, “I have three granddaughters. I’d like them to be able to take out their Constitution and say, ‘Here is a basic premise of our system, that men and women are persons of equal stature.’ But it’s not in there.”